Coffee – Washed Vs. Natural Process

Every day, we drink around 98 million cups of coffee in the UK. Yet, when you buy a bag of beans, the label often lists terms like “washed” or “natural” without explaining how they change your morning brew. These two processing methods are the single biggest factor in determining flavour.

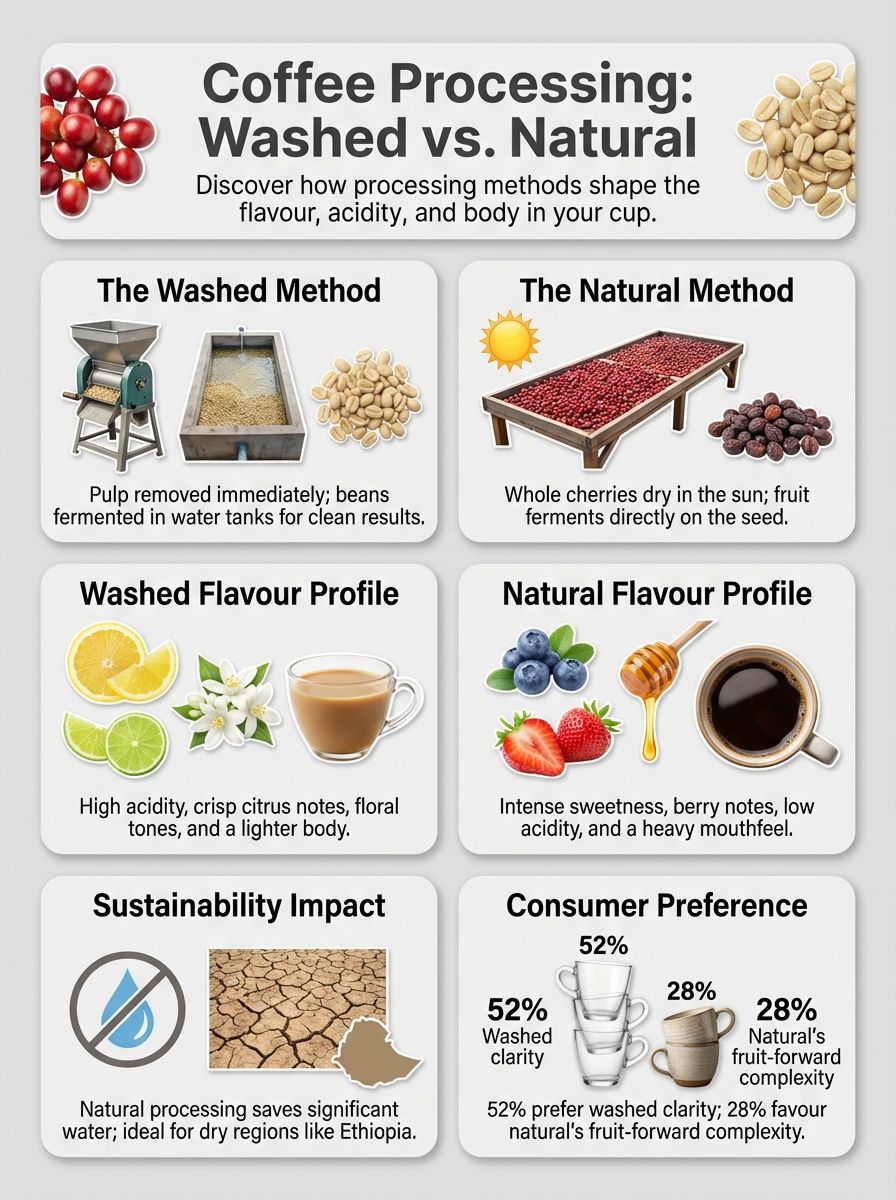

Washed coffee generally offers a clean, crisp taste with higher acidity, while natural coffee delivers a bold, fruity sweetness. Understanding this difference is the secret to buying beans you actually enjoy. This guide breaks down the science, the sustainability facts, and the insider tips you need to choose the right bag every time.

Key Takeaways

- Washed coffee uses water to remove the fruit before drying, creating a clean cup with higher acidity and bright citrus or floral notes.

- Natural coffee dries the bean inside the cherry, allowing fruit sugars to ferment into the seed, which results in intense sweetness and rich berry flavours.

- Producing washed coffee traditionally uses up to 40 litres of water per kilogram, whereas the natural process uses as little as 1-2 litres, making it a key choice for sustainable farming in water-scarce regions.

- UK trends for 2025 show a massive surge in natural processed beans, with Brazilian single-origin sales growing by 196% as drinkers seek out bold fruit-forward profiles.

- While 52% of drinkers still prefer the clarity of washed coffee, natural options are gaining ground for their complex, wine-like character and often command a higher retail price.

Understanding Coffee Processing Methods

Coffee production relies on different methods to separate the seed (the bean) from the fruit (the cherry). This step is not just mechanical. It is a chemical intervention that locks specific flavours into the bean before it ever reaches the roaster.

What Is the Washed Process?

In the washed process, producers focus on removing the fruit entirely before drying begins. It starts immediately after harvest, where cherries go through depulping machines that strip away the skin and pulp. The beans then enter fermentation tanks filled with water for anywhere between 8 to 72 hours.

This soaking phase is critical. It allows natural enzymes to break down the sticky mucilage layer clinging to the parchment. Once fermentation is complete, workers wash the beans thoroughly with fresh water to leave them perfectly clean.

The result is a bean that tastes purely of itself and its soil. You get a clean cup profile that highlights the specific region or terroir. This method produces consistent, high-quality lots, which is why it remains the standard for many premium roasters. However, it is resource-intensive. Traditional setups can use up to 40 litres of water per kilogram of dried coffee, posing challenges for farms in regions like Guatemala or parts of East Africa.

What Is the Natural Process?

The natural process, also known as the dry process, is the oldest method of preparing coffee. Instead of stripping the fruit away, producers spread the whole cherries out on raised beds or brick patios to dry in the sun. The fruit flesh remains on the seed for up to four weeks until moisture levels drop below 12 percent.

During this time, the fruit ferments like a raisin. The sugars and fruit esters migrate into the bean, altering its cellular structure. This creates a bean that is physically denser and chemically richer in sugar.

“Natural processing is a high-risk, high-reward game. If rain hits the drying cherries, mould can ruin the entire crop in hours.”

This method is essential for arid regions like Ethiopia, Yemen, and the Cerrado region of Brazil because it requires almost no water—often less than 2 litres per kilogram. The trade-off is the need for rigorous labour. Workers must hand-turn the cherries constantly to prevent spoilage, ensuring the final cup tastes sweet and fruity rather than fermented or “oniony”.

Key Differences Between Washed and Natural Coffee

The choice between these two methods changes everything from the environmental footprint of your cup to the price you pay at the checkout. Here is how they compare on the factors that matter most.

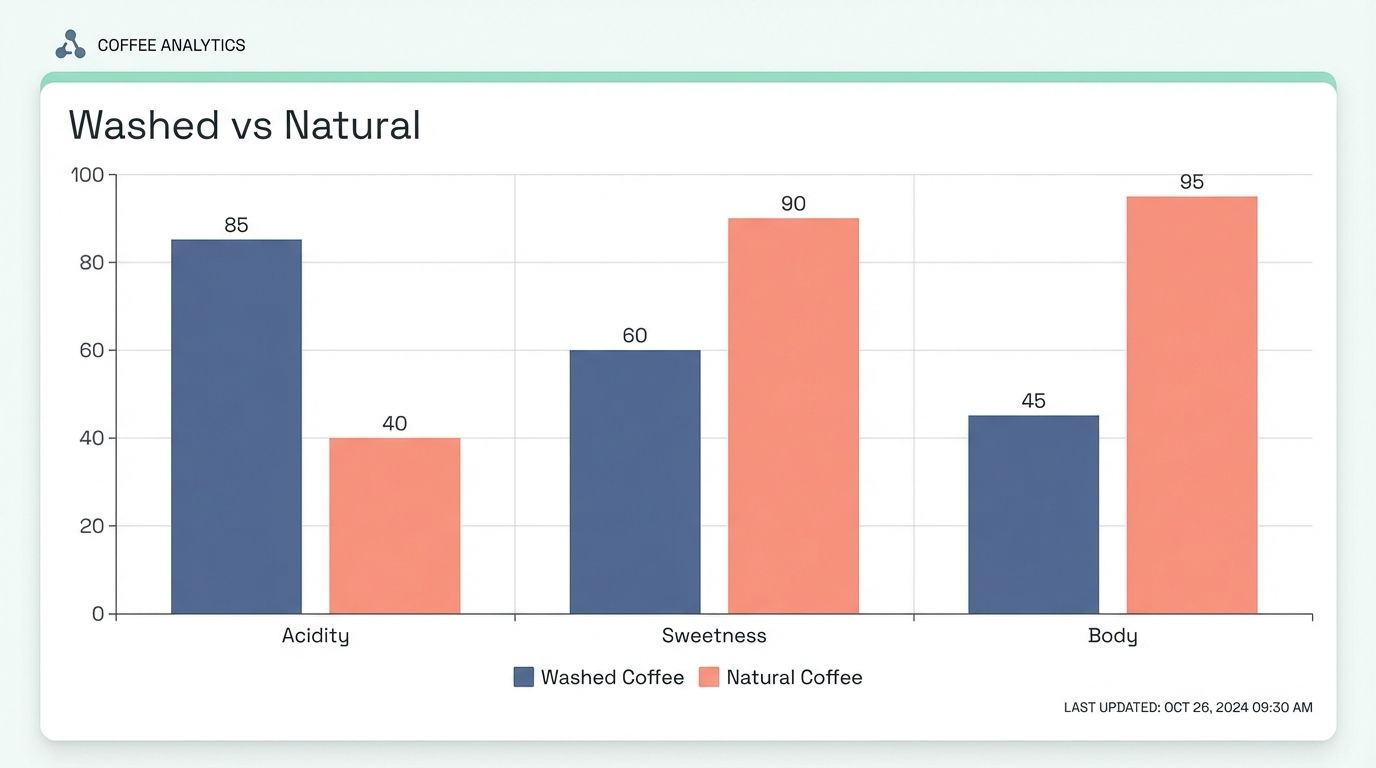

Flavour Profiles and Acidity

Washed coffees are the “white wines” of the coffee world. Because the fruit is removed early, you taste the bean’s intrinsic acidity and clarity. You will often find notes of bright citrus, crisp apple, or floral aromatics. It is a crisp taste that appeals to those who drink their coffee black or want a refreshing, tea-like body.

Natural coffees are the “red wines”. They have a heavier body and lower acidity but compensate with massive sweetness. You can expect fresh fruit notes like blueberry, strawberry, or even tropical funk. In the UK market, these beans are increasingly popular for espresso blends because that extra sugar creates a thick, syrupy crema.

| Feature | Washed Coffee | Natural Coffee |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Flavour | Clean, acidic, floral, citrus | Sweet, fruity, berry, heavy body |

| Mouthfeel | Light to Medium (Tea-like) | Full, Syrupy, Creamy |

| Consistency | High (Reliable flavour) | Variable (Can be “wild” or “funky”) |

| Common Origins | Colombia, Kenya, Central America | Ethiopia, Brazil, Yemen |

Environmental Impact and Sustainability

Water usage is the biggest dividing line. Washed processing is effectively a water based system. While modern “eco pulpers” can reduce usage to under 10 litres per kilogram, many traditional mills still consume vast amounts of freshwater. This can pollute local waterways if the fermentation wastewater is not treated properly.

Natural processing flips this script. It uses negligible water, making it a champion of sustainability in drought prone areas. In fact, data from Brazilian cooperatives like Expocacer indicates a massive shift toward these methods to meet “regenerative” farming goals. UK buyers are supporting this; orders for regenerative coffee, often using natural or low-water methods, nearly tripled in 2025.

However, natural processing carries coffee production risks. It requires consistent sunshine. An unexpected rainstorm can rot the fruit, leading to financial losses for the farmer. This risk factor is why high grade natural coffees often cost $1-3 more per pound than their washed counterparts.

Choosing Between Washed and Natural Coffee

Your preference usually depends on how you brew your coffee and what you value in a cup. Do you want reliability and clarity, or are you looking for a flavour bomb?

Which Process Suits Your Taste Preferences?

If you brew with a V60, Chemex, or other filter methods and drink your coffee black, start with washed beans. You will appreciate the separation of flavours. Washed coffees allow you to taste the specific variety of the bean without the distraction of heavy fruit fermentation. Around 52% of drinkers still lean this way because it offers a classic, clean coffee experience.

If you prefer a French Press, espresso, or drink your coffee with milk, natural coffee is often the better buy. The intense sweetness and fuller body stand up well to milk, tasting like a fruit dessert rather than sour fruit juice. This is why sales of single-origin Brazilian naturals have surged by 196% in the UK recently; they offer a smooth, chocolatey, and fruit-forward profile that is very approachable.

Insider Tips for Buying

When shopping for specialty beans, look for specific clues on the bag to predict what you will get:

- Check the Roast Date: Natural coffees fade faster. Try to buy them within 4 weeks of roasting to catch the strawberry and blueberry notes before they turn woody.

- Look for “Honey Process”: If you cannot decide, single origin beans marked as “Honey” or “Pulped Natural” are a hybrid. They offer the sweetness of a natural with the clarity of a washed coffee.

- Be Wary of “Funky”: If a tasting note says “boozy,” “winey,” or “fermented,” it is likely a natural or anaerobic process. This can be delicious but polarizing.

Newer experiments like anaerobic fermentation are pushing these boundaries even further. These beans ferment in sealed tanks without oxygen, creating wild flavours like cinnamon or bubblegum. While exciting, they can be overwhelming for a daily cup. For a safer bet with a heavier mouthfeel, stick to a classic natural from Brazil or Ethiopia.

Conclusion

The difference between washed and natural processing methods is the difference between a crisp apple and a fruit compote. Washed beans give you clean and bright tastes that highlight the skill of the farmer and the quality of the soil. Natural processed beans deliver bold fruit notes and a sweetness that can transform your espresso.

Next time you are in a cafe or browsing online, check the label. If you want consistency and acidity, go washed. If you want texture and sweet complexity, go natural. Your choice supports different farming traditions and sustainability efforts worldwide, so drink what tastes best to you.

FAQs

What Is the Main Difference Between Washed and Natural Processed Coffees?

The main distinction lies in the drying phase: washed coffee is depulped and left to ferment in water for 12 to 72 hours to break down the mucilage before drying. In contrast, the natural process—the oldest method—leaves the whole cherry to dry with the bean inside for up to four weeks.

How Does Processing Affect Acidity Levels in Coffee?

Washed coffees typically offer a cleaner cup with higher levels of acidity and citrus notes because the fruit is removed early. Natural processed coffees tend to have lower acidity and a heavier body, often showcasing wine-like or berry flavours.

What Happens After Coffee Cherries Are Harvested Using Each Method?

Washed beans are dried in their parchment after fermentation, whereas natural beans remain encased in the dried fruit pulp until they are ready for hulling.

Is Honey Processed Coffee Similar to Washed or Natural Methods?

Honey processed coffee often bridges the gap by depulping the cherry but retaining a specific percentage of sticky mucilage—known as Yellow, Red, or Black Honey—during the drying phase. This retained fruit flesh increases sweetness and body compared to washed coffees, without the intense fermentation of naturals.